iDanae Chair quarterly newsletter: Causal Machine Learning

The iDanae Chair (where iDanae stands for intelligence, data, analysis and strategy in Spanish) for Big Data and Analytics, created within the framework of a collaboration between the Polytechnic University of Madrid (UPM) and Management Solutions, has published its 4Q20 quarterly newsletter on Causal Machine Learning

iDanae Chair: Causal Machine Learning

Analysis of meta-trends

The iDanae Chair for Big Data and Analytics (where iDanae stands for intelligence, data, analysis and strategy in Spanish), created within the framework of a collaboration between Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM) and Management Solutions, aims to promote the generation and dissemination of knowledge, the transfer of technology, and the furthering of R&D in the Analytics field.

One of the lines of work developed by the iDanae Chair is the analysis of meta-trends in the field of Analytics. A meta-trend can be defined as a value-generating concept or area of interest within a particular field that will require investment and development from governments, companies and society in the near future.

This quarterly report addresses causality in the field of machine learning models and its impact on the development of these models.

Introduction

Machine learning techniques are proving to be very useful and applicable for all kind of business, which explains the important development and growth they are showing. In the field of machine learning there are different problems: some are oriented to the search for patterns, behavioural biases, etc., while others are aimed at making a specific prediction.

In this second type of problems, there is usually a cause or a set of causes that constitute a causal system, and that explain a specific result. Therefore, it is important to know and understand this system. However, machine learning techniques are not developed to discover or understand the causal relationships. Causality is understood as the relationship of cause and effect, so that the occurrence of an event (the cause) has as an effect the occurrence of another event. Therefore, machine learning techniques are not designed to understand this cause-effect relationship. For example, these techniques could detect a correlation between the fact that it rains and the fact that people carry umbrellas, but not associate the latter fact with a direct cause of the former. As a result, and due to the need to be able to understand the models and the predictions made by them in order to generalise their use and develop new applications, research into causality within the field of machine learning is a subject that is becoming increasingly important.

Causality research is not exempt from debate, and even the concept of causality itself is subject to controversy within the scientific community. In the academic field, there are different trends: (i) some researchers completely renounce to the use of this concept, arguing that it is impossible to determine causalities; (ii) other researchers argue that the capacity to think causally is one of the main factors of human intelligence that has allowed civilisation to progress. The latter also postulate causality as a basic and fundamental pillar for achieving progress in the development of artificial intelligence.

Within the field of machine learning, when dealing with problems that are based on a causal system, for example for prediction problems, one of the key assumptions on which the techniques developed are based is the hypothesis that if it is possible to understand the past it will be possible to predict the future. This understanding, however, must be causal: a non-causal understanding generates a process of overfitting, in which a model learns about the past in a perfect way, but is unable to detect the causal relationships that will be maintained over time and that will allow it to predict the future.

A simple example that illustrates this might be the following: consider an artificial intelligence system that tries to learn how to leave plates on a surface, and its testing environment is a room with a metal table and a parquet floor. After many attempts, the system will eventually find a relationship: if it leaves the plate on the table, the plate is not damaged, but if it drops the plate where there is no table, the plate falls to the floor and breaks. This is trivial if the AI thinks about it causally. However, if only the patterns obtained in the learning process are analysed, the system can associate the breakage of the plate with the location of the table, or with the fact that the floor is made of wood, and therefore predict that the plate will break if the table is moved, or if it is made of wood. This can be solved by training with different locations, or with different types of table and floor materials, but if after that new training a shelf is placed, again the system will not know what will happen. It needs a causal reasoning that allows the AI to generalise the information obtained from its experiments.

Despite some timid beginnings throughout the 19th century, the study of causality only began to develop formally a few decades ago, as it lacked the tools and specific language that would allow it to conduct a research as a discipline. The application of this branch of science to artificial intelligence aims to achieve models with (i) a much greater capacity for generalisation than at present and (ii) the possibility of ruling out spurious and biased relationships:

- Including in the modelling the understanding of the underlying causes allows to generalise the patterns found in training data sets over new data sets, even if these differ significantly from the training ones.

- The information obtained from the data through machine learning models is, a priori, more objective than the possible analyses carried out by human beings. This allows, therefore, a more adequate and fairer decision-making. However, the training data from these models may contain hidden biases for the developers, which can lead to unfair decisions about certain individuals based on variables of a sensitive nature (gender, sexual orientation, etc.). Understanding how, and especially why, one sensitive variable influences other variables in the training data is critical to eliminating bias. For example, a model may associate a higher correlation between the occurrence of lung cancer and being male, when the real underlying cause could be related to the financial resources available. This can be avoided by a causal understanding of the patterns found in the data.

Causality description

The correlation vs causality problem

One of the first aspects addressed in the analysis of causality is its differentiation from the phenomenon of correlation. From a formal point of view, it is understood that a variable A causes variable B if and only if at least one element of the pair (A,¬A) causes at least one element of the pair (B,¬B)8. Causality is transitive (if A causes B, and B causes C, then A can be said to cause C), anti-reflexive (an event A cannot cause itself) and antisymmetric (if A causes B, then B is not a cause of A). Correlation, on the other hand, is a statistical measure that identifies associations between variables. Some of these relationships may have a causal interpretation, but the measure of correlation cannot determine by itself if a causal relationship actually exists. In the case of a correlation relationship, it does not determine which variable is the cause and which variable is the effect. The correlation between two variables reflects the degree of cross predictability between both.

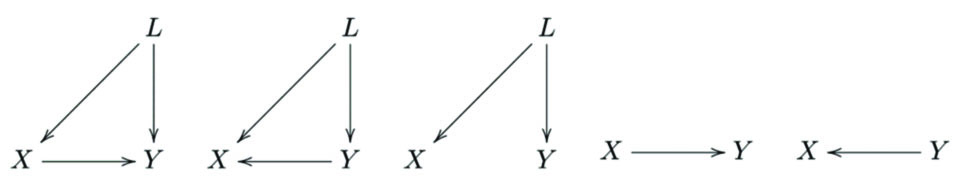

Correlation establishes a relationship between two variables that is weaker than causality. While the causality of one variable over another is uniquely determined through a single relationship between events (X→Y), the correlation between two variables allows for the existence of various relationships between them. Spurious correlations can occur, which are situations in which two variables are correlated without having any kind of causal relationship.

In a previous publication, the differences between correlation and causality and the problems that are generated when modelling and making predictions were introduced. The existence of a correlation between two variables does not imply causality between them, and the correlation can even be reversed by introducing the effect of a third variable (known as the Simpson paradox). The distinction between correlation and causality is therefore essential as a preliminary step before addressing causality analysis. This is why within causality research a three-level framework is established where intelligent systems could be categorised according to their ability to determine causal relationships.

The three levels of causality

The establishment of a framework for analysing the causal capacity of an intelligent system (whether an artificial intelligence or an organism) makes it possible to identify three levels of capacity. Each level corresponds to a higher capability, and can solve problems that are impossible at a previous level.

These levels are:

Association level: this stage includes the tasks of observation and search for patterns. It is the level of correlation. Most living beings are at this level, as are all the artificial intelligence systems that have been developed today. An example of this level would be a mouse that receives an electric shock when pressing a button and stops pressing it.

Level of intervention: this phase includes checking the existence of a causality by changing one of the elements of the system, leaving the rest constant. Only some animals are at this level. An example of this level would be to carry out a study on the effectiveness of a medicine by administering the cure to a set of patients and a placebo to another set of similar characteristics.

Counterfactual level: this stage is characterised by the capacity for abstraction. The understanding of the tools used is greater, which allow to understand why they work, and how to proceed when they do not work. It is at this level that the human being is found. An example of this level would be the human capacity to develop scientific theories.

To be able to develop artificial intelligence systems with a much greater predictive capacity than that currently achieved, it is necessary to provide these systems with tools so that they can model causality. This will not only have an impact on their performance, but will also make these systems more robust, adaptable and interpretable. To achieve this, the classic approach has been to design experiments to obtain causality relations in controlled environments to test a certain hypothesis, such as the use of control groups; while the Bayesian approach, which is more widely used in the field of machine learning, has consisted of the development of Bayesian networks.

Causal models

As stated, in those problems with an underlying causal system that explains a result, it is important to incorporate causal models with machine learning models. This incorporation can be done in a cyclical process: A model that explains a causal system (deterministic) can be integrated with a machine learning model, that detect patterns and correlations from data. These patterns can be explained by part of the causal system, and therefore can lead to the identification of new causes, which in turn can be incorporated into the deterministic model. Therefore, it is important to have big data systems that allow the analysis of all the data produced for the search of these correlations.

For example, if a computer system failure occurs, it is important to analyse the system of causes that have led to this event, and this can be done by studying data from servers, communications, routers, connections, users, etc. Once this data is analysed, causal models that allow explaining the failure can be completed, and therefore, it will be possible to avoid possible failures in the future.

The creation of a causal model makes it possible to describe the causal mechanism of the system under study. This facilitates the investigation of the system and may even avoid some field tests or experiments. A causal model consists of two elements: (i) structural equations, composed of a set of endogenous variables and a set of exogenous variables; and (ii) a set of functions that determine the value of the endogenous variables as a function of the rest of the endogenous and exogenous variables, which has an associated graph, known as Bayesian network.

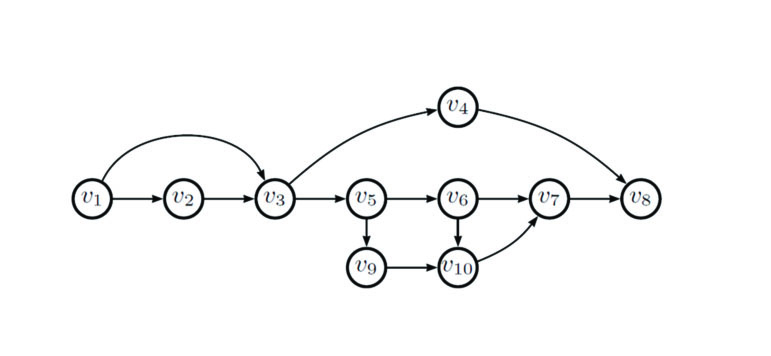

Bayesian networks

Bayes' theorem has been widely used in the field of probabilistic inference. However, when inferring probabilities between variables that are not directly related to each other, or for a large number of variables, the procedure, although possible, becomes tedious, while its computational cost increases due to the large numbers of connections. To solve these difficulties, Bayesian networks were developed at the beginning of the 1980s. These networks encapsulate the conditional dependencies among the variables by means of a directed acyclic graph, where the edges of the graph represent the direct influences among the variables. Structural equations are associated to the graph by identifying each node with the sets of endogenous and exogenous variables and the edges with the set of functions.

The connection between the networks and the probability distributions of the events is given by the Markov condition, in which it is established that each node in a Bayesian network is conditionally independent from all the nodes that are not connected to the node itself. From a causal point of view, this implies that a node is independent of all the direct causes or effects of the node itself. This connection, thanks to the Markov condition, makes Bayesian networks especially useful for predicting the probability of one of the possible causes for a given event occurring.

Causal models for Artificial Intelligence

The use of a causal model makes it possible to solve several problems in the development of artificial intelligence systems due to the following reasons:

- Interpretability: the ability to systematise the causal assumptions allows the creation of more transparent models, so that the user can analyse these assumptions and determine whether they are plausible or not, or whether new assumptions need to be added.

- Counterfactual formalisation: structural equation models and graphical representations allow the systematisation of counterfactual reasoning, which makes it possible to better determine causes and effects.

- Transmission of changes: this allows changes in cause variables to be transmitted to the effect variable, also allowing intermediate variables to be identified, so that the appearance of this type of variable implies the transmission of effect among other two variables.

- Adaptability and validity: the causal knowledge of the patterns in the data allows the systems to adapt to situations where they have no experience (i.e., they have not been trained on them), thus obtaining models that are more robust.

- Missing data: in the causal models it is possible to determine relationships even if there are missing data when certain conditions are met, allowing the production of consistent estimates.

- Causal findings: finally, the achievement of causal relationships that may be unknown up to now, by presenting sets of possible causal models that fit the training data, allows new explanatory variables to be obtained in the model.

Conclusions

The study of causality has experienced recent development, not being until a few decades ago when it was formalised as a field of study. The development of causal models based on structural equations and Bayesian networks has given a great boost to causality research, providing powerful tools for the identification of causal relationships and allowing simple modelling.

In the resolution of problems that present a predictive objective and that are based on the existence of systems of causes, incorporating the capacity to make causal discoveries seems to be a relevant requirement for achieving the long-term goal of true Artificial Intelligence. In the short term, this capacity will make it possible to obtain more robust, generalizable and interpretable Machine Learning models that can better deal with unknown situations that differ from the data with which they have been trained. Greater causal knowledge, and therefore greater interpretability, will also allow greater use of these models in regulated sectors or to carry out functions around which there are currently various ethical debates.

The "Causal Machine Learning" newsletter is now available for download on the Chair's website in both Spanish and English.